Discover more from Life in the 21st Century

Upon reaching the Missouri’s great falls, the Corps of Discovery delayed a month preparing to portage the river’s impassable obstacles. Here at the top of the plains, they were met with numerous tumultuous summer storms with hefty sized hail that bruised and battered exposed expedition members. Lewis writes of an afternoon for Clark,

“On his arrival at the falls he perceived a very black cloud rising in the west which threatened immediate rain. He looked about for a shelter but could find none without being in greater danger of being blown into the river should the wind prove as violent as it sometimes is on those occasions.

“At length about one-quarter of a mile above the falls he discovered a deep ravine where there were some sheltering rocks under which he took shelter with Charbonneau and the Indian woman (Sacagawea), laying their guns, compass, etc. under shelving rock on the upper side of the ravine where they were perfectly secure from the rain. The first shower was moderate, accompanied by a violent rain the effects of which they did but little feel. Soon after a most violent torrent of rain descended, accompanied with hail. The rain appeared to descend in a body and instantly collected in the ravine and came down in a rolling torrent with irresistible force, driving rocks, mud, and everything before it which opposed its passage. Capt. Clark fortunately discovered it a moment before it reached them and seizing his gun and shot pouch with his left hand, with the right he assisted himself up the steep bluff, shoving occasionally the Indian woman before him who had her child in her arms. Charbonneau had the woman by the hand endeavoring to pull her up the hill but was so much frightened that he remained frequently motionless. But for Capt. Clark both himself and his woman and child must have perished. So sudden was the rise of the water that before Capt. Clark could reach his gun and begin to ascend the bank it was up to his waist and wet the watch; and he could scarcely ascend faster than it rose till it had obtained a depth of 15 feet with a current tremendous to behold. One moment longer and it would have swept them into the river just above the great cataract of 87 feet, where they must have inevitably perished. Charbonneau lost his gun, shot pouch, horn, tomahawk, and my wiping rod; Capt. Clark his umbrella and compass.”

The Frenchman Charbonneau, who cooked well, seemed fairly lacking in other skills and a temperament necessary for such an expedition, unlike his Shoshone wife, Sacagawea, who traveled the entire trip carrying her new born infant. Charbonneau had previously bought her from a tribe on the plains after she had been taken by another peoples in a raid. Yes, the peoples across the Americas new slavery long before the Europeans and Africans arrived. When when one of the boats overturns, Lewis praises Sacagawea, “I ascribe equal fortitude and resolution with any person on board at the time of the accident.” He would remark later about her, “If she has enough to eat and a few trinkets to wear, I believe she would be perfectly content anywhere” – no modern American was Sacagawea.

Soon after the falls, the Corps would leave the river, swap their boats for horses, and head across the mountains to the Clearwater, Snake and finally the Columbia rivers. Upon entering the mountains, the vast herds of animals disappeared, passage was tortuous across a boulder and log strewn landscape, various roots provided their main nutrition.

Getting back on the water, the Columbia seemed much more densely populated than the Missouri. While the vast herds of mammals didn't exist on the arid Columbia plains, salmon densely schooled the waters. Down the river, dried salmon became the Corps overwhelming sustenance, making more than a few sick. In response, they bartered for plenty of dogs, which Clark stated many developed a taste for – don't tell ASPCA, we’ll be ripping Lewis and Clark signs down across the West.

The peoples west of the Rockies – Nez Perce, Chinook, et al seemed much less impressed by the Americans. But these weren't the first white men some had encountered and the Corps hard trip across the mountains left them with little to barter. Also, they must have looked quite the ragged bunch, not overwhelmingly foreign coming out of the mountains, now largely dressed in various deer and elk hides, floating down the river in their recently dug out canoes.

One thing for certain, the peoples of the Columbia seemed not to have a great respect for property, certainly nowhere near an early 19th century American’s. The constant snatching along with hard bargaining tried the Corps’ patience. Lewis opinion was much different of the people west of the Rockies than east. He had found the latter Shoshone “frank, communicative, fair in dealing, generous with what little they possess, extremely honest, and by no means beggarly. Each individual is his own sovereign master and acts from the dictates of his own mind.” Concerning the latter, he was not so praising, coming back up the Columbia Lewis’ humor had changed, but then anyone's would, in their almost five months winter camp along the Pacific coast, it rained all but 12 days.

With the coast’s sea and weather far too violent, Lewis wondered how anyone would name it the Pacific. They made camp in the estuary a few miles up river. When a whale washed up on a nearby beach, Sacagawea, who had not yet seen the ocean made her case to Clark to be part of the whale party, “that she had traveled a long way with us to see the great waters, and now that that monstrous fish was also to be seen, she thought it very hard that she could not be permitted to see either.”

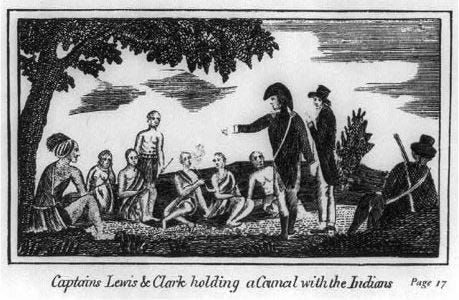

For the entire trip, the relations between the Corps and the people long residing on the land were for the most part friendly, if not at various times strained. Clark claimed one thing that helped most is they had Sacagawea and no war-party traveled with a woman, suspicions lessened. Only once, on their return, meeting up with a Blackfeet war party did violence ensue. Lewis shot and killed one man.

The trip to the Pacific coast Clark calculated as 4126 miles. It had taken 15 months, the journey back only six. On the return journey, Clark went down the Yellowstone, remarking once again of the plains’ animal populations, “For me to mention or give an estimate of the different species of wild animals on the river, particularly buffalo, elk, antelopes, and wolves, would be increditable. I shall therefore be silent on the subject further.” At the same time, Lewis explored a little north around the Marias River. “We passed immense herds of buffalo on our way; in short, for about 12 miles it appeared as one herd only, the whole plains and valley of this creek being covered with them.”

After 26 months, just above Saint Charles, Missouri near the expedition’s end, the Corps met an American Captain setting up river to the Platte with the ends of establishing trade with the Spanish in Santa Fe. Clark writes, “This gentleman informed us that we had been long since given out by the people of the United States generally and almost forgotten. The President of the U. States had yet hopes of us.”

The President was Jefferson, and his hope in the Corps a representation of the man’s, and new republic’s, always unbounded optimism. Also, Jefferson knew Lewis better than most, he had handpicked him. Maybe Jefferson was a better judge of character than his modern detractors give him credit, after all, he had a distaste, if not downright despising Hamilton, not that he had any great love of Burr either. “Fucking New Yorkers,” he was long known to have said.

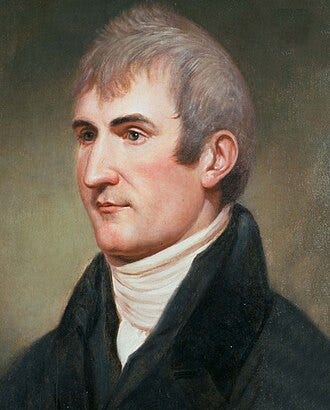

Nothing better represented the new republic’s character than the Corps of Discovery and its two captains. On his 31st birthday, in the middle of this fantastical trip, Lewis measured his life against the public virtues of the new republic,

“As yet done little, very little indeed, to further the happiness of the human race, or to advance the information of the succeeding generation. I viewed with regret the many hours I have spent in indolence, and now sorely feel the want of that information which those hours would have given me had they been judiciously expended. But since they are past and cannot be recalled, I dashed from me the gloomy thought, and resolved in the future to redouble my exertions and at least endeavor to promote those two primary objects of human existence, by giving them the aid of that portion of talents which nature and fortune have bestowed on me; or in the future to live for mankind, as I have heretofore lived for myself.”

Hell, today, that’s almost anti-American. Also in regards to the Corps and the new republic, in several crucial situations, they took a vote, both Sacagawea and York, Clark's enslaved African American servant, voted — that would be enfranchisement for women a century before they gained it and a century and half before it was gained by most African Americans.

In the end, it seems of all the then residents of the Missouri and Columbia rivers only the grizzlies had the correct foreboding what change these Americans and their guns represented for the land, its animals, and peoples:

“A little before dark McNeal returned with his musket broken off at the breech and informed me that on his arrival at Willow Run he had approached a white bear within ten feet without discovering him, the bear being in the thick brush; the horse took the alarm and turning short threw him immediately under the bear. This animal raised himself on his hinder feet for battle, and gave him time to recover from his fall, which he did in an instant and with his clubbed musket he struck the bear over the head and cut him with the guard of the gun and broke off the breech. The bear, stunned with the stroke, fell to the ground and began to scratch his head with his feet. This gave McNeal time to climb a willow tree which was near at hand and thus fortunately made his escape. The bear waited at the foot of the tree until late in the evening before he left him, when McNeal ventured down and caught his horse, which had by this time strayed off to the distance of two miles. These bears are a most tremendous animal. It seems the hand of providence has been most wonderfully in our favor with respect to them, or some of us would long since have fallen sacrifice to their ferocity.” – Meriwether Lewis

According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service there’s now less than two thousand grizzlies in the contiguous 48 states — there’s more Mohicans! “Grizzlies were reduced to close to 2% of their former range in the 48 contiguous states by the 1930s, with a corresponding decrease in population.” So, if I’m doing my math right, that was over a hundred thousand grizzlies at the time of Lewis and Clark, that be one big, baaad neighborhood. From a half-century ago, the grizzly population is up from 700, this increase often touted as one of those endangered species success stories and there’s not many, but, yeah, well, sort a, two thousand ain’t many, just ask the Mohicans.

Lewis, who was the naturalist of the trip, wrote the first fine analysis of this new to the Americans species, “It not uncommon to find two bears here of this species precisely of the same color, and if we attempt to distinguish them by their colors and to denominate each color a distinct species we should find at least twenty... The most striking differences between this species and the common black bear are that the former are larger, have longer talons and tusks, and will not climb a tree though hard pressed.”

Such a story, the great legends and innumerable stories of the American West just shaping, that world now completely gone. Today, maybe we need tens of thousands of new Corps of Discovery launched across America, to rediscover its people, flora and fauna, landscapes, and waterways, here in the 21st century.

Thank you.