Discover more from Life in the 21st Century

Banking & Money

Many years ago upon finishing William Greider's seminal history of the Federal Reserve, banking, and money, Secrets of the Temple, I thought to myself, “Oh man, it's all much more ridiculous than I imagined.” Years later in conversation I said to Bill, “That book taught me money was just created.” He laughed replying, “It's like telling people there's no god.” That's been my experience ever since.

The idea that money is just created, at its core nothing more than an article of faith, is the Temple's greatest secret. This is a truth that in no way denigrates money's power, in fact just the opposite, money is one of humankind’s greatest political inventions. Inherently being nothing more than an article of faith, a matter of trust, has made money neither no less valuable or useful. After all, Solon explained two and half thousand years ago trust is the basis of all society.

Debt preceded money. Much farming has always relied on debt. Toward the beginning of the Agrarian Era, debt was provided and accounted by the state. With the Greeks and Romans debt was offered by wealthy individuals. At the beginning of the Renaissance, private institutional debt creation came about with the establishment of modern banking. Merchants proliferated in Italy and trade needed upfront money, paid back once the goods were delivered. One person's investment is always another person's debt.

With industrialization, banking evolved to be not simply about the trading of goods, but more and more concerned with their production and distribution. The Renaissance witnessed the establishment of banking, industrialization saw its reach spread across all aspects of society accompanied by the banks' growing power.

Banks make money by taking in money then lending it out, creating loans, i.e. debt. When a bank creates a loan, it's accounted on the bank's books as an asset, and here's where the magic starts, that asset can then be used to create more loans. In modern economies this is the fundamental mechanism of money creation. The value of that paper dollar in your pocket, on a plastic card in your purse, or on everyone’s phone, is all based on bank-debt.

Banks don't and have never stored much money in their vaults. No bank profits on money sitting in a vault. Most money that comes in the door, quickly exits back out the door in the form of a loan, allowing the banks to create more loans. On any given day, a bank has available only a tiny fraction of the deposits on their books.

The most amusing part of all this, money, an article of faith to begin with, is even more so anytime you look at your bank balance. Depositors all believe their money is in the bank, but in reality the bank possesses in cash an amount closer to what’s necessary for an average number of days of business. As George Bailey tried explaining to his panicking Bedford Falls customers, their money wasn’t in the vault, it was in the various loans of everyone shouting and panicking beside them. When bank faith is tested with a “run” or “panic,” the bank is in trouble. No bank can survive a big enough run, A bank's loan assets can be instantly called to provide cash.

The 19th century is filled with bank crises due to panics, along with plenty of failures caused by banks making too many bad or fraudulent loans, all part of the process that established bank-debt money as the currency of the land. In the first decade of the 20th century, a major panic hit the US financial systems. Panics instantaneously dry up liquidity. The Wall Street Journal recently defined liquidity as “the capacity to trade quickly at quoted prices” - that’s about as good as any definition. Panics crash established prices. What was worth a dollar at the beginning of the day, might only be worth 50 cents that evening. Panics feed off themselves. Lower values induce more selling, more selling creates lower values generating more selling. In a market system, value has no objective measure. Value is dependent on collective subjective value bestowed by a given market’s participants. Lack of liquidity causes prices to fall.

In reaction to the 1907 Panic, the Federal Reserve system was founded. With the Fed’s creation, US finance became not just a system of loosely connected separate banks, but an integrated institutional money system. As conceived at the time, the Fed's Job 1 would be providing money, that is liquidity, in times of panic, in order to alleviate selling pressure and keep values from crashing. How did it work? Not so great, 15 years after Fed's creation came the worst financial panic and banking crash in modern history. This financial crisis created a series of New Deal banking reforms, resulting over the next four decades in the most stable period of banking in American history.

Several things were key to this stability. The first was limiting leverage, limiting the bank’s loan creation ability using any given dollar, forcing the banks to keep a certain fraction of cold hard cash in reserve. The second was separating money, such as prohibiting using saving deposits for speculation on Wall Street, keeping commercial banking’s creation of loans separate from investment banking’s incessant trading. Finally, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was created, allowing the average depositor to feel their money was secure no matter the bank's fate, small deposits would be backed by the full faith and credit of the United States government.

Starting in the 1970s and continuing for the next half-century, many of these New Deal regulations were loosened or eliminated. Bank leverage exploded with the creation of various nefarious financial instruments. Money was allowed to mix, main street money such as savings mixed with Wall Street money, pumping-up not just speculative but fraudulent money. By the mid-80s, the banking system began to wobble, becoming increasingly unstable, first with the developing world debt crisis and then culminating two decades later with the great crash of 2008.

As instability increased, leverage was not reined in, nor were the various components of the money system separated. Each time the financial system quaked, finance doubled-down on the actions that caused the shaking. Most importantly, the role of the Federal Reserve changed from at its founding of being the lender of last resort and stabilizing values in times of crisis to becoming the major player inflating ever more distorted values and disallowing any correction of these values.

The Fed became and remains a destructive value inflator, most egregiously inflating values over the last 15 years. The Fed is the banks, but unlike the banks who create money by creating debt, the Fed conjures money out of thin air, simple notations on the banks' electronic ledgers. The Fed's ever looser money policy combined with increasing regulatory laxity created an American economy drowning in debt.

At the top, most debt isn’t paid-off, just constantly refinanced. Total private and public debt rose from $3 for every $1 of GDP in the early 1950s to almost $8 today. For every dollar of real economic activity there's a debt claim of $8. The American economy is infested by parasites. Among other things, this massive debt inflates all asset values well above worth, simultaneously crippling the established economy from much necessary change.

Deregulated banking and the creation of mountains of debt have also facilitated a concentration of wealth to a degree never before seen in American history. Much of this wealth is actually debt, a lot of this debt is bad, so its not really wealth, nonetheless until written-off, wealth it remains. With apologies to historian Charles Beard, we created a system of perpetual debt for perpetual wealth.

Which gets to our present conundrum. After 15 years of historically loose money policy of low to zero interest rates, the Fed’s trying to raise interest rates to combat growing inflation. For the last several decades, the Fed’s been little concerned with the asset inflation they created, but when it comes to consumer prices and most importantly wage inflation – “You shall not pass!” Unfortunately for the Fed and all concerned, that’d be everybody, the massive debt load cannot stay inflated without correlated loose money policy, thus, rising interest rates are increasing financial anxiety and begin, literally, to break the banks.

Judging any given bank's solvency, even in the best of times is not necessarily straight forward. A bank is solvent based on the qualities of its loans. If the loans are goods, the bank's more or less solvent. With a bank's most valuable assets, their loans, distributed across the economy, invested to generate funds not instantaneously available, bank solvency has always been a somewhat organic measure across time. This makes banks particularly vulnerable to liquidity problems, having enough money to meet costs presented in a limited time. Years ago, reserves, also used to limit leverage, would help liquidity, but reserves have gradually been, well, let's say deemphasized, to the point that two years ago the Fed “Board reduced reserve requirement ratios to zero percent,” in order “to support lending to households and businesses.”

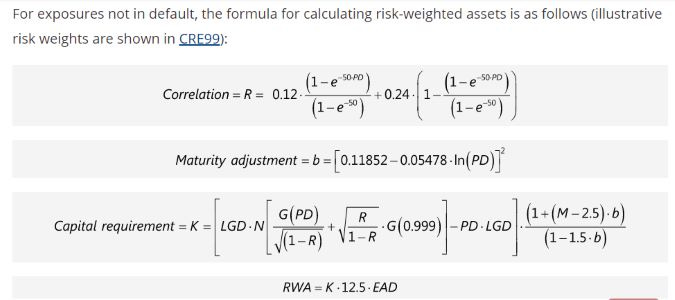

Over the last few decades, the importance of holding reserves was replaced by something called “capital requirements.” Capital requirements are lot more squishy than say having cold hard cash in reserves. Capital requirements are based on a small percentage of what's considered the bank's equity – all very subjective with all sorts of magical accounting using mathematical models creating risk-weighted assets.

Having become a little rusty, not following the banks and their toxic regulatory regime for a dozen years, I turned to friend and bank analyst Chris Whalen for a little updating. With an introduction from Bill Greider, I met Chris 15 years ago during the last bank crisis. Chris had been an analyst for the Fed and for years has poured over the banks' books. In reply to a question on current accounting methods of bank equity and capital requirements, Chris emailed,

“Equity is a balance sheet concept. The "capital" is kept in liquid assets like Treasuries and, yes, GNMA MBS and Fannie Freddie. Get the joke? Thus with QT, the FOMC deliberately impaired capital. ”

So, so ridiculous. If you don't get the joke, it's on you.

Last week in response to the failures of SVB and Signature Bank on the other coast, the Fed created the Bank Term Funding Program. They announced they would swap “eligible collateral” while “collateral valuation will be par value. Margin will be 100% of par value at book.” Nice deal if you can get it! Who needs reserves, when you can tap the Fed, swap loses and simultaneously keep debt value inflated. That’s a win-win-win.

So, bank solvency is today even looser, let's say similar to the results of just eating mangoes and drinking tequila for three straight days. Solvency comes to a head with liquidity problems caused most recently having to sell capital—debt—at a loss due to the Fed's rate rising combined with, just as importantly, runs initiated by depositors’ crises of faith. No bank can survive a big enough run.

Here lies the American banking system, dangerously concentrated in a handful of massive institutions with mountains of bad debt across their books, continuously sheltered by the Fed from any accounting. While saying so is in poor taste in most financial circles, it's no stretch to say the American monetary system is itself insolvent, but then there is the Fed. In theory, there should never be a liquidity problem large enough to force a systemic solvency crisis, however, most assuredly, the Fed's continued actions will induce plenty of problems for the currency itself.

Banks are institutionally integral to modern money, the main forces of money creation. In fact, bank-debt money was a healthy improvement upon ancient specie money — coins comprised of gold and silver. Bank loans, the process of modern money creation, are tied directly to the economy and not separate from it as with minting specie, which is one big reason crypto is actually a step backward. In the end, the value of bank-debt money is accounted by whether loans are paid back or not.

From its inception, money has been a very abstract notion, a nebulous medium representing various notions of value, communication, and information regarding economic activity. This last aspect is key for moving beyond present problems. Money as a provider of information about the economy is greatly impaired and increasingly devalued by ever expanding mountains of bad debt. Just as with every other aspect of politics, money is in desperate need of reform, though completely devoid of serious thinking and the will to undertake any reform.

Valuing money from an information perspective can be accomplished by evolving money equivalents containing specific information content that can be exchanged without having to first transform it into a greater abstract currency. In fact, in a society creating seemingly infinite amounts of information, such information currencies will prove not just valuable, but essential for directly valuing, transferring, and utilizing information.

In actuality, the really hard and little understood component of any such process would not simply be a matter of creating new media, but creating the human associations, the institutional organizations and communication processes capable of facilitating information currencies, structure far more participatory and distributedly networked then our present banking and financial institutions.

Banks are quintessential community organizations. A bank's wealth is truly, at all times, dispersed across the community, yet its organization is centrally controlled. Indeed the banking system today is so centrally controlled to be powerfully anti-democratic. For the first century of the American experiment, before being institutionally enfranchised by the establishment of the Fed, developing banks were opposed from Jefferson to the Populists for being anti-democratic. They gave the few the power to both determine economic development and “riot on the labors of the many.” Banks are archaically structured monetary institutions, creating a more distributed banking order would be an essential component of any democratic reform.

In the wise words of Bill Greider, as far as money goes, “There is no god.” It's time to lose faith in the temple, its priests, ceremonies, and practices, while rebuilding trust in each other, and sisters and brothers there is no more difficult a faith.

Further reading:

History of Money

John Kenneth Galbraith’s, Money: Whence It Came, Where it Went

Current Accounts

Whalen’s The Institutional Risk Analyst

John Authers, who was at the FT in 2008, now at Bloomberg

Yves Smith @ Naked Capitalism

And Dylan Ratigan knows as much as anyone, if he wants to write anything about it