Discover more from Life in the 21st Century

Einstein's War

The 20th century was one of the most revolutionary centuries in human history. Across the board – politically, culturally, scientifically, and technologically – humanity experienced radical changes. Fascinatingly, people rapidly adapted relatively easily to many of these changes, alarmingly, the past was even more quickly forgotten. No matter how radical the change, homo sapiens conceive the new as if it always was and was always destined to be.

In the first decade of the 20th century, a radical new human understanding of the world, indeed of the universe, was conceptualized by Einstein's theory of relativity. The theory, particularly its understanding of light, helped launch the formation of quantum physics, the science behind both the technologies of nuclear weaponry and the integrated circuit.

Mathew Stanley’s Einstein’s War is a wonderful popular history about how relativity first became known, sprinkled with some easy basic ideas on relativity. It took fourteen years after Einstein first published the special theory of relativity, (the general theory completed a decade later) for it to become simultaneously accepted in the physics community and popularly known. In between the theory and its acceptance came World War I. It would take a British astronomer named Arthur Eddington to both prove the theory and cross the political chasm developed by one of the bloodiest and stupidest wars in human history.

Without going into any detail about relativity, in a number ways it upturned established classical physics. Most have heard of special relativity's famous formula: energy equals mass times the speed of light squared (E=mc2). The “C” in the equation is the speed of light – a 186,000 miles per second. Few ponder its implications. Any given mass is comprised of immense quantities of energy, thus releasing a fraction of the energy in a softball sized piece of uranium or plutonium wipes out Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

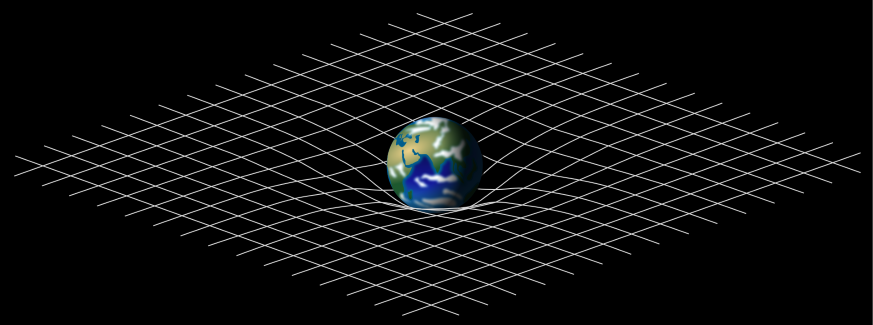

General relativity deals with gravity and the literal warping perspective of time as a fourth dimension of space, together all four dimensions are spacetime. Relativity perceives of gravity not so much as a Newtonian force as a curving of spacetime, perceptible with large astronomical masses such as stars and galaxies. One way to conceive of this is think about a bed sheet stretched taught in the air, then place a basketball in middle of it. A curvature of the sheet occurs around the basketball, that is what a star's mass, really any mass, does to spacetime.

According to relativity, if between your observation of a given star is another aligned star or galaxy, the light from the further star appears to bend. However, relativity's true divergence from the orthodoxy of classical physics is the light doesn't bend, but the star or galaxy actually curves spacetime, just like the sheet with the basketball, thus the light's path is really curved by following the curvature of spacetime.

This curvature is measurable, especially by a trained astronomer. It is most easily measurable with a solar eclipse, where the positions of stars close to the blackened sun can be measured in relation to their position in the regular night sky. Fortunately for Einstein, the study of solar eclipses had become more and more rigorous just as he birthed relativity. Unfortunately in 1914, when a group of German astronomers were ready to prove or disprove his theory with an eclipse cutting across the Crimea, WWI broke out. The Russians confiscated the expedition's equipment and tossed the Germans. Einstein and his theory would spend another five years in obscurity waiting for Eddington's proof.

In the telling of this five years of the war is where this book becomes truly valuable. Greatly to his own detriment, the derision of most of his German colleagues and the Kaiser's regime, Einstein was completely against the war, writing at its onset, “All of our exalted technological progress, civilization for that matter, is comparable to an axe in the hand of a pathological criminal.”

A Quaker, Eddington was just as opposed in England. Eddington's opposition can best be summed up by the Religious Society of Friends' statement released at the conflict's commencement, “We find ourselves today in the midst of what might prove (and did) to be the fiercest conflict in the history of the human race. We reaffirm that the method of force is no solution to any question.…”

World War I was the largest and most ridiculous war that should have never happened. The war to end all wars set up the even bloodier and far more destructive Second World War. What's most valuable about this book is it documents the war hysteria that infested all sides during the war. For any contemporary American, it's similar to the perpetual bellicose ambient buzz incessantly propagated by the National Security State that reaches various belligerent crescendos with any direct conflict.

In my life, the great acute hysteria that seized England and Germany can only be compared to the total delirium at the time of 9/11, which was insidiously promoted and eventually stupidly exploited. I remember losing a lot of respect for a number of people during this time. So it was interesting reading of the comparative frenzy that shook England and Germany and how very few, even in the scientific communities escaped its irrational clutches.

The greatest lesson of this book is essential for the present era and future. Specific knowledge or proficiency in any given aspect of life in no way confers greater insight into any other aspect of life. Nor is any accepted intelligence immune from irrational societal storms, most especially any requiring a measure of courage to stand against. An English journalist wrote of the war's impact on the established European intelligentsia, “The individual disappeared. The intellectual nervous, distinguishing man of culture lost control of his feelings and belonged to the masses.” As that old Greek understood, man is by nature a political animal, and it needs to be added, courage is not a commodity value.

Fear is a very deep, ancient, nervous system adaptation, far older than homo sapiens, apes, even mammals for that matter. It's manipulation creates very powerful, instantaneous, irrational reactions, only countered by a rational measured assessment of the perceived threat. On opposite sides of the conflict, Einstein and Eddington stood against the war, while almost all their colleagues succumbed to war fervor.

Einstein always despised German nationalism and militarism to the point of becoming a Swiss citizen. At the start of the war, he moved to Berlin for a position. In a letter he wrote of the German war delirium, “Heroism on command, senseless violence, and all the loathsome nonsense that goes by the name of patriotism―how passionately I hate them.”

He was flabbergasted by his scientific colleagues promotion of the war, including his greatest champion Max Planck, the most revered physicist of the era, the first first to quantify quantum measures. Yet, Planck helped produce the jingoistic, anti-British screed by the German scientific community known as the “Manifesto of the 93.” As Planck savagely stated in a contemporaneous speech, “All the moral and physical powers of the country are being fused into a single whole, bursting to heaven in a flame of sacred rage.”

Einstein gave his name to a counter-manifesto, writing to its authors,

“Although I am convinced that the voice of the handful of the informed carries little weight against the lust for power of the mighty and the fanaticism of the many. I still welcome your manifesto with pleasure and am pleased to be permitted to add my name to it.”

Amazingly, right at the time Einstein put together his final thinking on relativity, he was largely ostracized for his anti-war stand inside Germany, while just being German made his theory unacceptable in England and elsewhere. “Einstein pointed out claiming relativity was a German science was actually wrong. He was a Jew, a Swiss citizen, and 'by way of thinking a human being and only a human, without special favor toward any state or national entity.'”

Eddington stood on the other side of the war. A respected astronomer, director of the Cambridge Observatory, and a Fellow of the Royal Society, his opposition stemmed from his Quaker background. As the body count mounted, the Quakers were increasingly vilified across England for their opposition to the war. For the first time, England instituted a general conscription. Eddington sought deferment based on his beliefs, but in the end was granted it by his superiors insisting to the military of Eddington's essential service in his present position.

However, he never shied away from public opposition to the war, writing at one point against the despicable propaganda of the British scientific community and government,

“Fortunately, most of us know fairly intimately some of the men with whom, it is suggested, we can no longer associate. Think, not of a symbolic German, but of your former friend Prof. X, for instance―call him Hun, pirate, baby-killer, and try to work up a little fury. The attempt breaks down ludicrously... The worship of force, love of empire, and perversion of science have brought the world to disaster.”

The death toll of World War I was somewhere around 20 million people, including troops and civilians, and many of Germany's and Britain's best and brightest. Before the war, the scientific community had been creating the first networks of true internationalism. Journals, conferences, and personal communications across national borders were common in all branches of science. As Eddington wrote,

“The lines of latitude and longitude pay no regard to national boundaries.... In the minute structure of the atom or in the vast systems of the stars is a bond transcending human differences – to use it as a barrier fortifying national feuds is a degradation of the fair name of science.”

Tragically, this all was destroyed, exemplified by Oxford astronomer H.H. Turner writing at the end of the war, “The German character was fundamentally contradictory, intellectual without being refined,... discipline its mind but cannot control its appetites, a pre-Asiatic horde.” He concluded, “The dilemma is inexorable: we can readmit Germany to international society and lower our standard of international law to her level, or we can exclude her and raise it. There is no third course.”

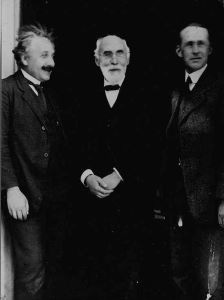

In the heat of the war, Eddington had come across a piece written about Einstein's relativity. Intrigued, he gathered all he could and soon understood full well the theory's radical implications, particularly for astronomy. He also learned Einstein was opposed to the war as much as he was. He quickly came to realize an opportunity presented itself to begin rebuilding the international science community.

A half-year after the war's end, Eddington led an English expedition to photograph a solar eclipse reaching totality off the African coast and across Brazil. The photograph's he generated decisively proved relativity's conclusions, the sun did indeed bend the path of light coming from the stars behind it.

Despite after all the war's animosities and prejudices, Einstein became an instant international sensation, fairly quickly he became the popularly beloved eccentric genius who moved the stars. An English journalist wrote,

“Virtually nothing but Einstein is being talked about here, and if he were to come over now, I think he would be celebrated like a victorious general. The fact that a German's theory was confirmed by observations by the English has, as is daily becoming more evident, brought the chance of collaboration between these scientific nations far closer. Thereby Einstein has done an estimable service to mankind, leaving quite aside the high scientific value of his ingenious theory.”

Eddington concluded,

“The most valuable contribution to a reconciliation of the nations and a permanent fraternity of mankind is in my opinion contained in their scientific and artistic creations, because they raise the human mind above the personal and national aims of a selfish character.... The intellectuals should never weary of emphasizing the internationally of mankind's most beautiful treasures and their corporations should never stoop to foster political passions by public declarations or other demonstrations.”

The war's end unleashed political turmoil in Germany, overthrowing the Kaiser. Einstein noted in one of his journal entries “class canceled because of revolution.” He added a little too hopefully, “Militarism and the privy-councilor has been thoroughly obliterated.” Einstein's known anti-war stance and political sympathies also turned his personal situation inside Germany upside down. He ironically and wryly noted, “Yesterday's heroes are coming fawningly to me in the opinion that I could break their fall into emptiness. Funny world.”

Funny world indeed. Einstein's War's greatest value is understanding no individual or group of individuals necessarily hold any great insight outside their own specializations, or at times even inside them. Nor does scientific knowledge in any way necessarily confer any special wisdom on how it should be technologically applied. Fritz Haber, one of history's greatest chemists, developed the Haber-Bosch process that pulled nitrogen from the atmosphere for producing fertilizer, creating much of today’s industrial agriculture. Simultaneously, he proudly developed Germany's chlorine gas program initiating chemical warfare.

Einstein's work became the foundation of quantum physics. Twenty years after Eddington’s proof of relativity, at the outset of World War II, Einstein included his name on a letter to Franklin Roosevelt warning the American president the recently discovered process of nuclear fission could be used to create weapons of unprecedented magnitude.

A century after relativity's revolutionary insights, technologies developed using them radically alter both the earth's landscape and human life. War hysteria remains rampant as ever and still as powerfully a destructive catalyst as it was century ago. Our politics remain inept in almost every way dealing with it.

Subscribe to Life in the 21st Century

History, Science, Energy, Technology, Environment, and Civilization