Discover more from Life in the 21st Century

I am a son of the proletariat. My father’s occupation on my birth certificate is “machine operator.” For over a quarter of a century, James Costello worked in a non-union factory on the South Side of Chicago until being unceremoniously laid-off. The plant was first operated by the Visking Corporation, but bought-out by Union Carbide. They manufactured meat casing using a process known as “viscose.” The casing was produced from wood pulp and cotton cellulose, extruded into various shapes, strung through chemical baths, dried, coiled into rolls, and then shipped to be used for mass producing sausage, hot dogs, and various lunch meats.

The plant was a cavernous building half a city block long and wide filled with a variety of machines. My dad worked on one of the final machines. It was half a football field in length. He worked at the front-end atop a six-foot high platform rising beside a giant tub of sulfuric acid. Lines of already formed casing of various sizes came across the ceiling down to his machine. He would string the lines into a multiple roller system that guided the casings up and down four or five times through the acid bath. Moving out of the bath, excess liquid and gas was squeezed out, then the casing ran forty yards through a massive dryer, and finally spun onto spools at the machine's end. Here another person worked, threading each new spool and placing the full spools in boxes for shipping. Depending on the width of the casing there could be a dozen lines or so rolling through the machine at one time.

At my dad's position, once set up, and the machine was running well, there wasn't much to do. Every once in while, you'd quickly run a razor vertically across the rolling casing to let out excess gas built-up. Literally hours could pass where there wasn't much to do but stand there and watch. They wouldn't let you read, nor could you could leave the machine unattended for long, problems might quickly develop at anytime.

My dad worked swing-shift. My mom told me he originally did it because he got 10 cents an hour more. On swing-shift you worked: seven days 8am-4pm, two days off; seven days 4pm-12am, two days off; and then seven days 12am-8am, three days off – the “long weekend” — then start all over again. I did it for one summer, your body and mind never adjust. Physically and mentally you're on a different plain than the rest of the world, like getting off work at 8am and going to have a beer, or getting off at midnight, you're not going to sleep until five or six in the morning.

My dad's schedule made him a unique father on the block. There were plenty of weekdays he was home, though any number of those days he was sleeping. Our house was sort of a neighborhood center. We'd have to tell other kids, “Be quiet, my dad's sleeping.” If he wasn't, he might well be out with us.

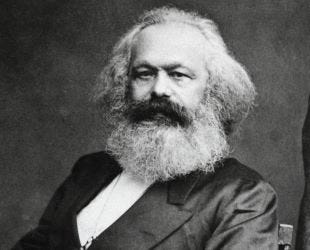

In his and Engels' Manifesto, Marx wrote,

“Owing to the extensive use of machinery, and to the division of labour, the work of the proletarians has lost all individual character, and, consequently, all charm for the workman. He becomes an appendage of the machine, and it is only the most simple, most monotonous, and most easily acquired knack, that is required of him.”

That was one thing Marx certainly had right. My dad or any worker in that factory and other plants across the South Side claimed no identity from their work. “Machine operator” was simply a job. When I worked there for a summer, everyone talked about how much time they had left to retirement as if it was a prison sentence. “I got three years.” “I got ten.” “I don't want to think about it.” My father was always trying to figure how to get out, do something else.

On the South Side, identity was gained through family, religion, and community, not profession. The provincialism of such places strengthens those ties. For me, my parents were insistent, “You're getting an education, going to college. You don't want to do this work.” And while school was certainly excruciatingly tedious and boring, it was easy, so graduating was a no-brainer, especially if it meant not having to walk through those plant gates at 65th and Narragansett every day.

My second year of college, I first got involved in politics, spending nine months working on Teddy Kennedy's run against the incumbent Democratic president for the party's 1980 Presidential Nomination. The last month of the campaign I was headquartered in Los Angeles – “swimming pools, movie stars” – as Field Director for Southern California. It was about as far away as one could get from the South Side. We did convincingly win the California primary, unintendedly helping usher in the Reagan Revolution.

The campaign took place as the de-industrialization of America switched into a higher gear. Soon, very few would be able to drop-out of high school in their second year as my father had, then get a factory job allowing them to support a family. During the campaign, I learned the history of labor in America. It took me a few years after to understand Kennedy's campaign was one of the last blasts of labor as an organized political force in America. Organized labor was in a rapidly accelerating decline.

The Democratic party and labor provided me with an initial political identity. It was where I came from, the people I grew-up knowing, family, friends, and community. But over the rest of the 1980s, trying to be on the Democratic party’s and organized labor's side, especially in Illinois, was an increasingly difficult proposition. Things were changing, organized labor wasn't. The Democratic party was mostly dissolving, professionalized by money, polls, and thirty second ads.

Illinois was an industrial state and at this point the whole of American industrial labor was on the wrong side of history, a losing numbers game. The Bureau of Labor Statistics notes, “US Manufacturing's share of nonfarm employment peaked in May 1953 at 32%. In June 1979, manufacturing employment represented 22 percent of total nonfarm employment, that share fell to 9 percent by June 2019.” The loss of manufacturing and its jobs resulted from offshoring by corporate globalization and through automation.

For decades, political opposition to both processes was anemic to nonexistent. In recent years, as reactionary forces have grown across large swathes of the country economically ravaged for a half-century by deindustrialization, labor has shown a little, I wouldn't go as far to call it life, but a little political interest has grown. However, this is a political dead end. Industrial labor, the general idea of organized labor as a societal political force is a worthless anachronism.

Unfortunately, our history deprived politics, most depressingly misguided young people, attempt to resurrect not just the idea of labor but the Old Moor himself along with whatever might be deemed socialism – an always very squishy proposition, especially when defined by its most zealous proponents.

Understanding the history of labor, socialism, and Marx is like opening one of those Russian Matryoshka dolls, one nestled inside the other. Obviously, the industrial labor force was created by industrialism. However, socialism's agrarian roots preceded industrialization. Marx used industrialization to redefine socialism, wrongly claiming his socialism was scientific as opposed to its “utopian” forebears.

Marx's thinking had all sorts of wrong headed ideas and fatal flaws. First, in one of the great misreading’s of history, he relabeled industrial labor, “the proletariat.” A term derived from the Ancient Roman republic, proletariat was a census designation for economically disenfranchised citizens, who did nothing but “reproduce.” For most of the republic's history, Rome was largely comprised of small farmer citizens, but as its empire grew, land ownership was increasingly consolidated. Ever more in debt and away fighting the latest war, the majority of small farmers lost their land to ever larger entities, then ended up in Rome. Here they became the proletariat, an economically disenfranchised, politically enfranchised citizenry reliant on the state for food, housing, and entertainment.

The last word in the world you could use to describe the Roman proletariat was revolutionary. They defined for history mob and rabble. In the republic's last decades, the proletariat were simply political and battlefield fodder for Roman patricians engaged in a decades long, republic destroying civil war over personal power. At any given time, the proletariat offered their support to whichever patrician offered them the best deal. They were the vanguard of decline, nothing more.

Thus, Marx's “dialectal materialism,” a deeply flawed formula for looking at history, needing an antithesis to his capitalist thesis, imagined his revolutionary proletariat. Despite his and his adherents insistence on his theories' scientific integrity, as Engels proclaims in an 1882 Manifesto introduction, “This proposition, which, in my opinion, is destined to do for history what Darwin’ s theory has done for biology,” the proletariat were a utopian construct. A necessary theoretical construct to manifest a synthesis for a theory of history narrowly defined as “class struggle.”

Marx dreamt the proletariat as a vanguard revolutionary force with lack of class conscious to be provided through party organizing. In his fatally flawed dialectical mysticism, he wrote,

“But not only has the bourgeoisie forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons ― the modern working class ― the proletarians.”

Of course this never happened, nor will it ever happen. Most amusing, in the two biggest countries where Marxism was empowered, the Soviet Union and China, the dictatorial regimes had to themselves create an industrial proletariat out of their overwhelmingly agrarian societies. While in the most industrialized nation, the United States, the industrial proletariat largely disappeared in a matter of decades.

Not that Marx didn't have some keen insights of then developing industrial capitalism, yet these too had some glaring deficiencies. He understood technology played a leading role in industrialization, and better than most, or even all, had astute understanding of technology's role in the social destruction of everything that came before it. In the 20th century, Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, evolved Marx’s understanding writing, “This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in.” Like Marx, Schumpeter thought this destruction would eventually destroy capitalism. However, today its waved as another adolescent banner inscribed “disruption” – We disrupt, therefore we are.

Marx's greatest fault regarding technology was generalizing it into one value – the “means of production.” Marx's whole theory is based on whoever controlled the means of production had power. He wasn't necessarily wrong about this, but again, it was far too narrow a lens to view technology and its role in human history. Any adapted technology changes many more aspects of society than just the means of production. For example, controlling the means of production certainly gave Ford and General Motors immense power, but the necessary infrastructure changes the automobile instituted and the changes of daily life evolved atop them transformed society to a much greater degree than simply control of the means of production.

Marx's greatest fault, no means his alone, was placing paramount measure for industrial value on labor. The real keys to industrial value are first and foremost energy, particularly the burning of fossil fuels, and then technology. Energy is only mentioned in passing in his Manifesto, “Thereupon, steam and machinery revolutionised industrial production.” With the rest of Marx’s theory energy is simply another commodity, it was always so much more than that.

Outside the 20th century's communist states, what developed as socialism would best be described as Bismarkism, after the 19th century German Chancellor, who not only forged the German state out of blood and iron, but the Western welfare state, including national health, welfare, and retirement programs. Bismarkism became 20th century European socialism and its weaker American cousin, New Deal Liberalism.

Marx was actually well ahead of and dismissive of this process, critically writing,

“The aristocracy, in order to rally the people to them, waved the proletarian alms-bag in front for a banner... In political practice, therefore, they join in all coercive measures against the working class; and in ordinary life, despite their high falutin phrases, they stoop to pick up the golden apples dropped from the tree of industry, and to barter truth, love, and honour for traffic in wool, beetroot-sugar, and potato spirits.”

The Old Moor could turn a phrase, no better critique of 20th century American Liberalism.

Industrial labor never became the vanguard of political change envisioned by Marx. Not in any society did it even come close to being a majority of the society, nor will it ever. The US Chamber of Commerce states, “In 1950, the average worker was producing goods averaging $12,600 in value each year. That total doubled in faster increments, until by 2011 that same worker was making goods worth $153,000 a year.” Technology and energy have always been the driving forces of industrialism, not labor.

Industrialism radically transformed society. Its infrastructures, processes, and institutions now entrenched obstacles to in any way healthily engage changes being wrought by new technologies or dealing with industrialism's legacy problems. Dividing the world into labor and management instantly created a system of labor subservience, whether managed by capitalists or socialists. Industrial categories like labor and management, socialist and capitalist, offer little help in understanding the 21st century.

The category of industrial labor – “the proletariat” – never transferred well. For example, it was always somewhat problematic in relation to civil servants. Nor is it helpful for understanding more recently formed, information technology created, centrally controlled distribution systems. Such challenges are not going to be met by organizing Amazon's workforce, but breaking Amazon to pieces while simultaneously rethinking how necessary goods are distributed, which also means rethinking how and what's made.

The same thing can be said for the various massive servants industries developed over the last decades. A healthy politics is not about organizing McDonald's workforce, but removing meal preparation out of the economy, placing it back into the home and neighborhood. Looking at this issue from an industrial labor perspective provides little insight or hope for the future.

We need to be slow to categorize. Many old categories are no longer helpful. Instead, we need to universally adopt an understanding of the fundamental existential commonality of our species and our shared history upon this very small planet. The greatest scientific political fact is the equality of the human experience in regards to the fundamental components of life — food, shelter, health, and sociability. We hold them in common no matter how you want to categorize by gender, race, nationality, labor, or capitalist. Today, the common human experience continues to be radically transformed by two centuries of revolutionary technological development and energy use. This transformation has not simply impacted human life, but the ecology of the entire planet, the ecologies that birthed us.

My dad would have been 94 today. He's dearly missed by all who knew him. He was a very beautiful sweet guy, with a wonderful sense of humor, honest, and hard working beyond description. He was a devout Catholic who loved his family, his life, and the Cubs, more or less in that order. His job as machine operator defined him not at all.

Subscribe to Life in the 21st Century

History, Science, Energy, Technology, Environment, and Civilization

Sounds like a great guy. I worked that same machine for one summer in 1974. It was enough of a push to motivate me through college. They must have changed the policy on books, because I read a few that summer waiting for the rolls to to fill.