Discover more from Life in the 21st Century

The Exxon takeover of Pioneer had me take a little closer look at oil numbers, something I haven't done for a number of years. From its peak in 1970, traditional US oil production declined for the next four decades from 9.6 million barrels a day (mbd) to 5 mbd in 2008. That summer oil hit a record high of $150 dollars a barrel, launching the Shale Revolution. Ironically, it wasn't just the price of a barrel that launched shale, but the great debt boom begun three decades before. Though briefly collapsing in 2008/2009, debt reflated to ever greater heights over the last fifteen years, providing, amongst other things, the funding for shale.

For over a decade, the shale industry lost money. Scott Sheffield, the head of Pioneer, who just unloaded his company for $60 billion to Exxon, said just a couple years ago, shale’s “been an economic disaster, especially the last 10 years. Nobody wants to give us capital because we have all destroyed capital and created economic waste.” At the time, Pioneer was filing for bankruptcy to restructure their debt. The San Antonio Express-News wrote Pioneer “hasn’t posted a quarterly profit since 2014.” Boy, it was almost a dot.com or crypto play. When it emerged from bankruptcy in 2020, Pioneer had $2 billion in debt. Exxon just bought a Pioneer with $5.2 billion of debt, a doubling, almost tripling in three years. Yet, the FT says of the last couple years, “Gone were the days of debt-fuelled drilling binges and in their place was a focus on shareholder returns.” I guess, but sure seems shale still pumps plenty of debt along with any oil.

How precisely all the shale industry's losses were accounted has never been made quite clear, but then how losses are accounted in this era of infinite, instantaneous electronic compute debt seems as mysterious as the rising and falling of the Nile was for the Ancient Egyptians. It wasn't any great technological development, be it horizontal drilling or fracking, that made the Shale Revolution, it was a massive flood of debt.

All said, without question there was mucho oil in America's shale patch, and still is plenty, not anywhere near the amount in the deserts of Arabia as its proponents and Mr. Sheffield once again promotes in his glowing profile in the FT. It also wasn't cheap and that's without accounting the environmental costs for the 100 thousand holes punched in Texas, Oklahoma, North Dakota, New Mexico, et al. just in the last decade. But then we've never accounted oil’s environmental costs beginning with the first well in Pennsylvania. Historically, shale is humanity’s last great industrial act. Here’s what it takes to punch and frack each hole:

Multiply this by 100,000 and you can see why it ain’t cheap. Scroll around the Permian using Google Maps and look at all those little white squares, shale wells, spread tightly across western Texas and eastern New Mexico.

PBS recently ran the headline “U.S. oil production hits all-time high, conflicting with efforts to curb climate change.” In regards to conflicting efforts, EIA's announcement today of new natural gas-fired capacity additions expected to total 8.6 gigawatts in 2023 needs to be added. Call it Bidenomics or Bidengreen, OK that’s unfair, you'd long be hard pressed to find an American elected official of whatever shade coming out against shale or natural gas.

America's oil production is indeed at record highs, 3 mbd above 1970, but there's a couple caveats. First, shale isn't that old bubbling crude coming up through the ground, you know, black gold, Texas Tea. Much of what's pulled out of the American shale patch is referred to by the industry as “oil equivalent.” For example in its last quarterly report Pioneer states it produced 369 thousand “barrels of oil” per day and another 340 thousand “oil equivalent.” The simplest understanding of the difference is the oil equivalents contain less energy (less dense) than plain old crude.

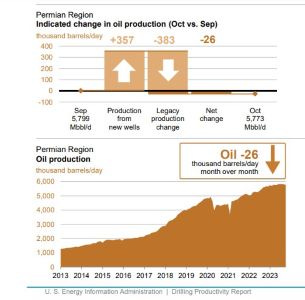

Secondly, traditional oil, non-shale, the 5 mbd in 2008 is now down to 3.9 mbd, that's a decline of over 20%, while the growth of shale has slowed considerably. Shale's great growth years were during the Obama and Trump years, where for five years it impressively grew double digits, anywhere between 14% to 17% a year. In the last two years it grew a combined 7%, having fallen the previous two as demand fell with the Covid shutdown and debt was squeezed. The most recent EIA numbers show the growing trend of Permian new wells not keeping up with the declining production of the old wells:

Well, the best recent American energy news the Wall Street Journal reports, “Automakers Have Big Hopes for EVs; Buyers Aren’t Cooperating,” maybe a real discussion can begin about moving beyond our oil infrastructure, after all it’s only a century old. That simultaneously requires a serious revaluation of the money system, which increasingly provides little value at all.

Subscribe to Life in the 21st Century

History, Science, Energy, Technology, Environment, and Civilization