Discover more from Life in the 21st Century

Oyinbo Analysis of the Nigerian Election (I)

After the 2004 Dean campaign, Trippi would ask me to do other campaigns. I'd refuse. The only reason I participated in that campaign was because I was so disgusted and angry at the criminally stupid Iraq war. For the previous dozen years, I hadn't dealt electorally with Democrats. I hadn't missed them.

A few years later Trippi was doing work in Africa, specifically in Nigeria with then Vice-President Atiku Abubakar. Atiku was an essential opponent preventing former military dictator and first elected President of Nigeria's Fourth Republic, Olusegun Obasanjo, from seeking an unconstitutional third term. Going back to its Greek roots, keeping tyrants out of power is pretty much democracy Rule #1.

Speaking to Trippi at the time, I told him “Forget campaigns here, but you have any work in Africa, I'm in.”

Nigeria is one the places on the planet best representing the human experience in the 21st century. It is the most populous nation of the African continent with a very long history, an oil power to boot. At that point, the only Nigerians I had ever met were two big fellows ahead of me changing money at the UN Sustainability Conference in Johannesburg in 2002. Impeccably dressed in agbadas and topped with cowboy hats, they pulled from their pockets giant wads of American dollars to change to South African rand. Nigeria was a place to visit.

Trippi helped elect Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan in 2011. Jonathan hailed from the southern Niger Delta state of Bayelsa. He was of Ijaw ethnicity, not one of Nigeria's three largest peoples – Hausa, Yoruba, and Igbo. He was up for reelection in 2015. Trippi called and asked if I still wanted to go to Nigeria, “Get me a ticket.” A few weeks later touched down on an international runway, jet propelled, I'm living in the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Nigeria did not disappoint on any level. A beautiful country filled with intelligent hardworking people, cursed with oil, and burdened by a government structure that for all sorts of reasons doesn't work. Not by coincidence, the Nigerian constitution begins “We the People.” Nigeria's borrowed federal structure fails not only Nigeria today, but increasingly the American republic that first introduced it. In 250 years, the US has done little to restructure its now obviously archaic government structure. It's not difficult to discern it doesn't work in Nigeria.

Nigeria is a British creation from back in the imperial sun never sets days. From the 17th century and the Slave Trade, the Brits had forts along the coast. In the mid-19th century, they occupied Lagos. At the end of the 19th century's Berlin Conference, the Europeans sliced up Africa, the Brits got Nigeria. A couple decades later, they united the colonial North and South with Lagos, this became Nigeria. Lagos became the administrative and commercial capital of the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria, as always, with the greatest irony, who was to protect Nigeria from the British?

The Brits had long experience with Islam, particularly in India. Islam had reached Nigeria across the great sand ocean of the Sahara centuries before Christianity's arrival via the Atlantic. The Brits were more comfortable with the North's Islamic hierarchy than the more decentralized, freewheeling, one could even say democratic South. The North's Hausa people provided troops to help the Brits subdue the whole of Nigeria.

At the beginning of the 20th century coal was found in the South at Enugu, the heart of Igbo land. The coal wasn't used for Nigerian development. A rail line was built to bring the coal to the coast for export, a tradition followed fifty-years later with the discovery of oil. Oil was discovered with the Empire's collapse, its development bears the stamp of corporate big oil and America. The vast majority of Nigeria's fossil fuels have always been exported, not burned for the advantage of Nigerians.

The Empire didn't build much Nigerian infrastructure, a few rail lines and some roads to better control and loot Nigerian resources. As far as government, the Brits left a rotten, top-down colonial structure, the Nigerians still struggle to rid themselves of its vestiges.

At birth, Nigeria was a plastic creation of the Brits, the North overwhelmingly Muslim, the South Christian, with more than a spattering of local animistic tradition everywhere. Nigeria is kaleidoscope of ethnicities, cultures, and languages – 250 is the figure thrown around. The three main language groups Yoruba, Hausa, and Igbo are internally culturally diverse and make up an estimated 60% of the population. 200 million or so is the number tossed around as total population, but this is just an estimate. The last attempt at a census was almost two-decades ago. One thing all Nigerians agree on is that census was worthless.

Economically, the majority of Nigerians remain subsistence, or just above, farmers. A significant segment of the population is tech-literate and an extensive, largely wireless, electronic communication infrastructure stretches across much of the nation. Paradoxically, the electricity infrastructure is far less extensive. The World Bank estimates 55% have “access to electricity.” Unfortunately, oil remains the government's main revenue source, proving continually problematic at best and tragic at worst, such as providing the means for the military to brutally control Nigeria for most of its independence.

In 1999, Nigeria's Fourth Republic (almost French, right?) was established. Military rule abolished. The election last Saturday, February 25th was the seventh since the end of military rule. The first four elections were won by the People's Democratic Party (PDP), basically Nigeria’s then establishment. The new republic's first president was Yoruba Olusegun Obasanjo, former general and military dictator from 1976-1979. His most infamous action as dictator was his troops throwing Fela Kuti's mum out a window. She would die from injuries received. Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was a Nigerian John Adams, Susan B. Anthony, and John L. Lewis rolled into one, an eminently important and healthy Nigerian political force.

When I landed in Abuja, the 2015 election was just beginning to get into gear. Jonathan was the incumbent, and on the African continent, and to be fair almost everywhere else, that pretty much assures reelection. The opposition had not yet united, their candidate not yet selected. The one thing I would hear over and over again from PDP was, “Don't worry, the opposition will fall apart.” It would turnout it was the PDP that was falling apart, finally collapsing this recent election.

Trippi thought former Vice-President Atiku would be the opposition All Progressives Congress (APC) nominee. The first Nigerian political event I attended was Atiku's announcement speech, a rollicking affair. No one at our office wanted to go. I finally cajoled a reluctant young colleague, who kept refusing saying, “It will be too rowdy.” It was, but not too.

However, it would be former dictator, Hausa general, Muhumadu Buhari, who would claim the APC nomination. Buhari had militarily overthrown the elected president of the Second Republic in 1983. He proved so incompetent, the military removed him in less than two years. However with the restored republic, Buhari had run in three previous elections as a devout Muslim, establishing in the North the strongest and most zealous political base of any Nigerian political figure. He lost each election, each time gathering more votes while establishing the still strong Nigerian tradition of immediately claiming his loss was resulted from “rigged” votes.

Buhari's 2015 campaign focused on corruption. No Nigerian will claim corruption isn't a problem. Oil's price was steeply descending the entire year before the election, always a problem for any sitting Nigerian government. The brutal Boko Haram were at their height, taking over much of the northeastern state of Borno and adjoining areas of several others. A few weeks before I arrived, a bomb exploded just down the street from our office in the capital.

Jonathan had problems, maybe the biggest, the PDP was beginning its descent into irrelevance. In the months before the election, a number of PDP governors in key states departed to the APC. Helping keep this diverse but growing opposition force together was Bola Tinubu, then former Governor of Lagos and today's president-elect. In the last three elections as the PDP fell apart, Tinubu helped keep the APC together. With Buhari heading the ticket, they won handily in 2015 and 2019. Last Saturday with Tinubu on top, APC claimed victory with a little over a third of the vote.

In 2015, I first became aware of the Lagos Asiwaju from his incessant bleating in the press about corruption, which from the source was a little rich. Mr. Tinubu became a very wealthy man off Nigerian politics and in return he's used plenty of this money politically. Warning's against rigging almost always followed, again amusing, seeing how Mr. Tinubu's voter suppression tactics have helped him keep control of Lagos for twenty years. Lagos is Nigeria’s most populous state and has the worst voter turnout. I was advised by a number of Nigerians, even the ones who didn't like the former Lagos governor, to nonetheless pay attention to him. What I discovered by the end of the 2015 election, unlike a lot of spokespeople politicians, Tinubu was politically skilled in the never easy process of keeping a coalition together, organizing, and counting votes.

In the 1970s, Mr. Tinubu went to college in Chicago, just blocks from where I was growing up. Who knows, I may have even shared a bus with him down 79th street on my way to high school, after all Bola didn't arrive in Chicago with the money he later gained as Governor of Lagos. His Chicago years were the last years of Mayor Daley's imposing political machine, it appears from his Nigerian political career, young Bola was paying attention.

Nigerian campaign structures are different than the US, actually more like the US before the rise of the campaign industry. Candidates are selected at the party's convention and then the party becomes the campaign. I was involved with an independent expenditure group, as they are called in the US, comprised of some of the president's close supporters. There were actually many such groups, so many it became a bit problematic to deliver a disciplined strategic message. With so many independent voices, the campaign message was far too diverse and diluted. Our group focused on Net communications and establishing a cellphone based voter outreach, ID, and Get-Out-the Vote operation, all new to most Nigerians. Keep in mind this was just fifteen years into the new republic and only its fifth election.

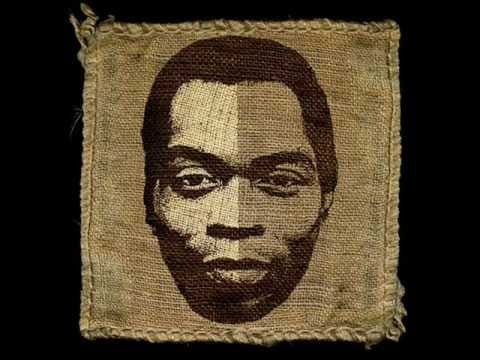

I shared an office, when he would drop by from everything else he was doing, with Ken Saro-Wiwa. Ken was the son of one of Nigeria's finest sons, Ken Saro-Wiwa Sr. The Saro-Wiwas were from deep in the Niger Delta. Ken Senior had been a very popular writer and successful television producer. He became one of the leading resisters to the Nigerian military junta's raping, wrecking, and looting of Nigeria in alliance with international oil companies. The Saro-Wiwas were of the Delta's Ogoni people, living at ground zero of oil’s environmental destruction. In 1995, for his resistance efforts, Ken Sr. was hung by the most brutal of Nigeria's military dictators, Sani Abacha.

Having actively followed global oil and environmental issues my entire life, I knew the Saro-Wiwas' story. Meeting and being able to work with Ken was a great pleasure. Ken represented many Nigerians I met, smart, knowledgeable, hard-working, wonderful smile, quick to laugh, with a biting sense of humor. One of the things I like best about Nigerians is they have great senses of humor. They always laugh at my jokes.

Ken and I had some great conversations. One concerned the question of Nigeria's population. The last census having been worthless, no one really knew. I always asked people what they thought the number was. Ken gave the lowest. He didn't think there were many more than 120 million, if that, which would still make Nigeria the most populous nation in Africa and near the top in the world.

Getting accurate information about anything in Nigeria can be incredibly difficult. They lack a well established public information infrastructure, which is one of the top priorities of any good government. Looking at any number put in front of me, I learned to first think if there was even the capability to accurately obtain it, much of the time not. Most frustrating was getting information from the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), which guarded the voter registrar and past election results as state secrets, two essential readily available public records if you're going to have any sort of viable elections system.

As always, in the last month before the election I was getting increasingly anxious. I had passed the distinct, four story, green, white, and red PDP headquarters numerous times over the months. I said to Ken, “Come on, let's go see what's happening over there.”

Ken looked at me and smiled, “Those guys are just having a good time.” Not reassuring.

When I expressed concerns to Trippi, he would say, “I don't know, PDP can turnout the vote.”

No doubt. In 2011, Jonathan had rolled to a twelve million vote margin, 60%-40% victory. In a US presidential election, that's a landslide. However this time things were different; Jonathan was less popular, there was a united opposition, and maybe the most changed, a Jonathan reformed INEC.

Subscribe to Life in the 21st Century

History, Science, Energy, Technology, Environment, and Civilization