Reforming Government: What's Up With That? (II)

In answering this question it's helpful to begin with historian Fernand Braudel's understanding of geography's essential role in shaping the history of Homo sapiens — “humanity's relation with the inanimate.” Additionally, this can be understood as the relationship of humankind with innumerable, distinct, sublimely animate ecological systems, all in part shaped by local geography. In an era in desperate need of coming to terms, to account for, much of the destructive ecological change manufactured by industrialization, representing these systems is an essential component to reforming government.

In the last two centuries, once great physical barriers to human interaction such as rivers, vast plains, mountains, lakes and ocean, were transcended and in part redefined. Yet across history, these same geographical barriers served and still do as the political boundaries of tribes, peoples, and nations. Simply by existing, these physical formations became political lines of demarcation. Fossil fuel transportation leveled and shrunk the planet, making once imposing physical barriers nonexistent. Many political borders defined by physical boundaries were surmounted, even liquidated.

However, both the Agrarian and Industrial Eras lacked whole understanding of the political power of the physical entity in itself, that is Braudel's relation of humanity to the inanimate. It might be argued humankind had a greater appreciation of this relation before industrialization, if nothing else of the raw physical power of any given topography. For example, this is clearly seen in the ten US states where the Mississippi River forms either the eastern or western borders. By simple physical imposition, the river creates the borders, however there is no enfranchisement of the entire river itself. Such disenfranchisement reveals itself at a far vaster scale looking at the entire watershed, a drainage including over half the states in the Union. Across the past, such topographies provided rational political borders simply through imposed physical boundaries, simultaneously ignoring the system as a whole.

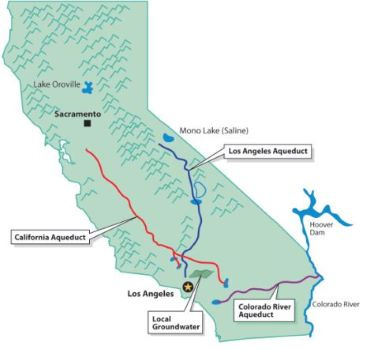

Another example is the essential geography of the State of California, especially in regards to life's elixir, fresh water. Most of the state is dependent on the Sierra Nevada mountains and the rivers of the two valleys on either side of the range for a significant volume of the state's water supply. The County of Los Angeles' ten-million people import 85% of their water needs, most of it coming from the two valleys to the north with an additional supply coming from the Colorado River to the east. Without imported water, the population of Los Angeles County couldn't be a million people.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Los Angeles Aqueduct, a marvel of industrialism, first grabbed the Sierras' water from the Owens River to the growing city. It was built by Los Angeles Water Department's William Mulholland, who in 1913 opened the spigot, commanding like a modern Moses to the wandering tribes of the desert, “There it is. Take it.” Thus arose the suburbs of the San Fernando Valley. A half-century later with the 444 mile California Aqueduct, Governor Pat Brown connected the San Joaquin River to LA, using pumps powered by fossil fuels to bring the water over the Tehachapi Mountains, resulting two decades later with the evolution of consumer America's cultural pinnacle, the Valley Girl.

The Owens Valley to the east of the Sierras, the Central Valley to the west, and the mountains themselves which form the great rivers have no political representation. The areas are crisscrossed by local, state, and federal political boundaries, none distinctly comprising the whole mountain range, rivers, or valleys, geographically the lines all arbitrarily drawn. The rivers’, valleys’, and mountains’ ecologies were radically altered, some would say destroyed, as the population of Los Angeles County, using the imported water, grew from three hundred thousand in 1910 to ten million people today. It's a premier example of industrial technology surmounting geography and transforming previously established ecologies.

In addition to these Californian systems was the great alteration of the Colorado River, LA's third imported water source. Specifically, the vast destruction visited upon the river's once vast delta both physically and ecologically, which happens to lie, across that most arbitrary of political lines, the US-Mexican border.

Geographically defined political lines drawn to represent geography and its varieties of ecological systems would necessitate a flattening of traditional centralized, hierarchical, political organization, in certain ways, a return to the republic's agrarian past. History has rewritten many of the original intentions of the American system. From the founding, power has been relentlessly withdrawn from local and state entities and into DC – maybe history's most powerful arbitrarily conceived political entity. One place modern republicanism failed was in not innovating a more horizontal power structure, instead evolving within a federal system a traditional pyramidal hierarchy, the base gradually subservient to the top. Power removed from the local hindered or made moot issues defined by an area’s immediate geography.

Instead of defaulting to age old pyramidal hierarchies, reformed republicanism can be distributedly networked with representation in part accounting the geography and ecology of the local nodes. Though seemingly obvious, it needs to be pointed out in the end all these systems can only be politically represented by people.

In regards to the Mississippi River system, local political entities can be structured with an understanding of local topography and ecological systems, then networked together with all the other localities representing the river's whole watershed. This allows each locality to best take advantage of their geography and local ecologies with constant input of the river’s watershed as a whole, developing technologies best advantaged to this diversity, not simple reckless adaptation to the technologies themselves, homogenizing greater systems around technology selection, instead creating more sophisticated governance through the enfranchisement of the greater environment.

Restructuring governance is certainly not historically unprecedented, the founding of the US and the resulting modern republicanism was just that. Yet, it might be two specific 6th century BC democratic reforms of the Athenian Cleishtenes that are most relevant. First, to get around established power, he expanded the number and enfranchised the 139 demes (maybe more). Each deme was the local, neighborhood if you will, government for the specific segment of the city. Each citizen became enfranchised through the deme, as opposed to previously through the larger four traditional tribes. The deme required direct citizen participation in all local decisions and their resulting implementation. The demes became the necessary foundation of all other democratic institutions such as the Boule and Assembly.

The Athenian polis was comprised of three principle geographic areas, city, coastal, and farming inland, Cleishtenes then networked the demes together in 30 districts called trittyes. Each trittys was comprised of demes from each of the three regions. Simultaneously, Cleishtenes expanded the traditional tribes from four to ten, each tribe was comprised of various trittyes. In effect, this was geographical networking based on the then constrictions imposed by physical meeting.

Today, technology allows both a transcending of physical meeting, but also a reestablishment of greater local control and a necessity for a deme physical connection, face to face interaction. Today, communication of information can transcend physical restriction, but without a corresponding deliberate political restructuring of the physical in relation to both geography and ecologies, technology will trample both, creating dangerously homogenized environments based only on the values of the technology.

At this point, the grave problems and inefficiencies of modern republican systems are increasingly detrimental to governance and society as a whole. To reform the archaic structures of established republicanism, one simple and radical step would be the enfranchising geography, Braudel's intimate political forces that fundamentally define who we are, resulting just as importantly with the enfranchisement of the ecological systems that define us and life itself.