Discover more from Life in the 21st Century

Göbeklitepe I

If you could time travel to a savanna in East Africa 150,000 years ago, take a new born infant from her mother's arms, bring her back to today, raise her in Brookline, Massachusetts, she could end up attending Harvard or MIT. Across her childhood she would be completely indistinct from any of the children she grew up with or any other person she encountered. As a member of the species homo sapiens, she would be indistinguishable from you, me, or anyone else. Physically, across all those millennia, we have changed not at all.

However, before you came back, you spend time observing the lives of people on that savanna. In almost every way the details of daily human existence would be extraordinarily different. There would be no technology besides a limited number of stone tools, sharpened sticks, and the ability to produce fire. Shelter would at best be rough, primitive. People would live in small groups, constantly migrating to follow herds of various animals or continually returning to known areas of high concentrations of fruiting plants.

Agriculture — farming and the domestication of animals — wouldn't appear for a 140,000 more years. Another five or six-thousand years later the first metals were forged. The greatest physical differences between the lives of the family of our adopted, or abducted child depending on your scruples, and her contemporary Brookline existence is technology, and that is all the difference. This is a concept difficult for people to come to terms with, though it'd be more accurate to say it is an understanding completely and universally absent from contemporary thought.

Our story, our past, especially our ancient past, has been exorcised from history. This is largely the result of technological development. With the innovation and then adoption of any given technology, the adopters gain certain specific physical advantages. With this technological advantage inevitably comes a sense of cultural, political, and moral superiority. Across history this is easily discerned from the first agrarian aristocracies to our latest Tech-mandarins. Historically, one instance can be explicitly exemplified by the technologically advantaged Europeans and their self-righteous and brutal interactions with the Americas, Africa, and well, really, the whole world. But let's not be racist, from day one, Europeans interactions with each other were and as we see today still are excessively brutal.

The history of homo sapiens is intricately and acutely defined by technology. Two and half million years ago, pre-human hominids began our gradual intimate relations with technology by developing stone tools and controlling fire. With the development of industrial technologies in the last two centuries and the mass scale harnessing of fossil fuels, technological development has come at a rate and voracity unprecedented in the history of our species.

Previous to the Industrial Era, our greatest technological transformation was the millennia long transition from hunter-gatherers to farming-pastoralists. From the time homo sapiens were birthed on the continent of Africa some 300,000 years ago until 10,000 years before the present age, we relied completely on hunting and gathering. This is the overwhelming majority of the human story. Today, outside a few, very small scattered groups, it is an extinct way of life. If tomorrow the technologies providing our current way of life were to vanish and we were forced to return to hunting and gathering, the entire human global population would precipitously collapse, so unrecognizably vast has been our reshaping of the planet's environment.

The great agrarian revolution, arguably still the most important transition of the human story, occurred over thousands of years. Despite industrial technological hegemony of the last century, billions of people still remain subsistence farmers and pastoralists. Almost all our present institutions and practices — political, government, economic, cultural – along with our dependence and subservience to centralized order remain firmly rooted consequences of the Agrarian Revolution.

In recent years, gaining an understanding of evolution, great advances in prehistorical archaeology, and with the tremendously speculative, highly politicized, but nonetheless at times valuable schools of anthropology, ever greater light has been cast on our transition from hunter-gatherers to farmers and pastoralists. This knowledge is essential to understanding who we are as a species, how we’ve come to where we are, and a perspective essential to help us meet the challenges arising from a new powerful technological era we irrationally and recklessly rush into, an era increasingly defined not at all by ourselves, but by the technologies.

In the last couple decades, a great marker of this great agrarian transition was found in Turkey, a few kilometers outside the charming city of Sanliurfa. It lies just above the Syrian border, nestled in the northern most reach of Mesopotamia between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, smack dab in the middle of the Fertile Crescent, an area long associated with homo sapiens’ domestication of wheat. Sanliurfa is known for its exquisite cuisine, as one of the legendary birth places of Abraham, and for one of Roman history's most inglorious defeats at the battle of Carrhae, under the doomed imperium of Crassus, who with Pompey and Caesar comprised the infamous First Triumvirate of the republic's final years. No stranger to history, Sanliurfa has newly become synonymous with the sublime archaeological site of Göbeklitepe.

Göbeklitepe was first discovered a half-century ago, but didn't come under extensive study until the 1990s with the work of German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt. The site’s structures and artifacts are of a 1500 year period between 9500 BC and 8000 BC, so 11,500 to 10,000 years before the present age. Göbeklitepe seems to represent an early aspect of the human transition from hunter-gatherers inherently nomadic existence to a more settled life associated with a specific place.

The area around Göbeklitepe is a vast landscape of beautiful rolling hills and endless plains. Today, tilled fields, pastures, and pistachio orchards abound. During the Göbeklitepe era, the area is thought to have been much wetter, populated by diverse and great numbers of wildlife, along with still wild grains such as wheat, and wild pistachio trees. On top of the region’s highest hill with tremendous panoramic views, Göbeklitepe's incredible structures were unearthed. Schmidt and the Turkish tourist board refer to them as the “world's first temples.”

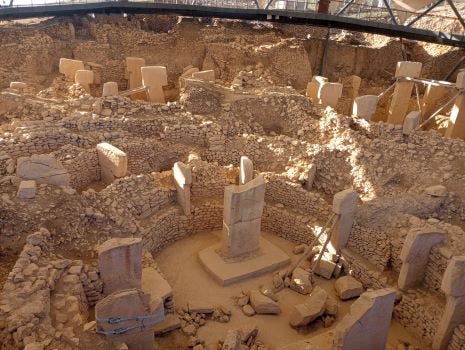

Having been privileged to experience many ancient sites across this planet, my initial impression was how small the site is. But slowly circling the surrounding path several times, a diameter of not much more than fifty or sixty meters, you develop an almost mystical sense of the ancient, an entirely foreign sensation, yet in some ways quite familiar. As Istanbul University's Necmi Karul commented, "When we put all this together, we see the construction of a new society that we have never encountered before."

To date, the majority of the excavation is six closely adjoined oval enclosures. The floors of each are leveled and smoothed bedrock of the hill, while surrounding each floor arise T-shaped carved limestone pillars, about an arms distance in separation, some reaching almost a height of twenty feet. Two main pillars face each other across opposite sides of each enclosure.

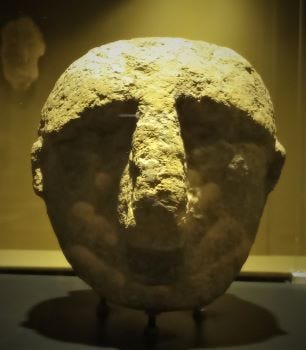

The pillars were all carved from limestone quarries not far from the site. On their surfaces are various reliefs of animal figures, including cats (lions or leopards?), aurochs, wild boars, ducks, vultures, snakes, and other animals. Maybe most intriguing on the sides of some of the pillars are sculpted bent human arms with hands. Taking it all in is nothing short of fascinating, “What was going on here 11,000 years ago?”

This is a question not easily answered and ripe for all sorts of speculation, which is OK. These rocks offer some telling story of human development. What is clear, this is one of the first places found where migratory hunter-gatherers began building permanent structures. Schmidt advocated,

"These people were foragers. Our picture of foragers was always just small, mobile groups, a few dozen people. They cannot make big permanent structures, we thought, because they must move around to follow the resources. They can't maintain a separate class of priests and craft workers, because they can't carry around all the extra supplies to feed them. Then here is Göbekli Tepe, and they obviously did that."

This raises all sorts of difficult questions about the gradual human settlement of specific places, including foremost the organizational capabilities of a pre-agrarian hunter-gatherer society to build such sites for what was necessarily, or maybe not, a largely migratory population. Schmidt believed the site was largely ceremonial and did not have dwellings. He died a decade ago and recent excavations have discovered dwellings, indicating it was also a settlement. However, it is clear that it developed before crop cultivation. Göbeklitepe demands a rethinking of established ideas that permanent human settlement derived exclusively from crop cultivation. Professor Karul states,

"The existence of tools pointing to agricultural experiments shows us that when the first settlements began to appear at the site, there was no agricultural activity, but wild grains were collected, and that this collection process evolved into the cultivation of plants over time."

Which is an idea overthrowing a century year old and widely held theory that farming came first and then settlement.

“Our findings change the perception, still seen in schoolbooks across the world, that settled life resulted from farming and animal husbandry. This shows that it begins when humans were still hunter-gatherers and that agriculture is not a cause, but the effect, of settled life.”

Subscribe to Life in the 21st Century

History, Science, Energy, Technology, Environment, and Civilization