Discover more from Life in the 21st Century

Göbeklitepe II

(Continued from Göbeklitepe I)

Göbeklitepe interacted with at least a dozen other sites in the immediate area. This whole area has come to be known as “Tas Tepeler” - Turkish for stone hills. “It is a fact that both Göbeklitepe and other settlements were sites part of an interacting social organization in a wide region about 11,000-11,500 years ago."

Göbeklitepe overthrows a lot of relatively new prehistory thinking of the last century by archaeological science, a relatively new science itself. It is a science in continuous search of, and in many cases never finding, hard evidence to support particular thinking. Göbeklitepe forces a rethinking of certain doctrinaire, pseudo-Darwinian theories that attempted to explain human civilization entirely resulting from selection by greater natural forces. A notion doomed from the start. Any understanding of human history comes with an appreciation of a certain freedom to act. Social, cultural, political, technological actions are in themselves quite powerful selection forces, though all these actions are influenced and in the end constrained by larger natural forces. Or a better way to think of it, all human actions are by definition natural forces, a lesson in desperate need to be learned or maybe relearned.

In this vein, Schmidt confusedly concluded a dozen years ago, "Twenty years ago everyone believed civilization was driven by ecological forces. I think what we are learning is that civilization is a product of the human mind.” It is not an either/or process, nor a synthesis producing dialectic, but an evolutionary both.

The whole Tas Tepeler era represents technological development. Karul states, “The beginning of settled life and living together in larger groups for the first time, brought a new social order, new relationships, and a division of labor,” all became exponentially amplified with agrarian life.

Technologies have two processes of selection. One is Darwin's selection by larger environmental forces. All technology is shaped one way or other by the laws of nature, none can oppose them. Secondly, there is a cultural selection process. Across our relatively short presence on this planet, humanity has been the one species to develop an increasingly complex culture that not only selects technology, but is defined by it. Established technologies become part of any future selection process. For example, without electricity there is no telephone, no television, no radio, no Hollywood, no rock and roll or hip-hop, and most recently there would be no computers, no internet, no electronic information tsunami radically transforming just recently developed industrial culture.

As the newest technologies radically alter industrial culture, humanity fails at almost every level to meet the challenges presented by our previous technological legacies. Across ten-thousand years, the Agrarian Era made radical changes to the ecologies that had birthed and sustained homo sapiens for three hundred-thousand years previously. Today, you can't find a lion from a Göbeklitepe pillar anywhere in the Middle East. However the wild wheat found at Göbeklitepe was gradually domesticated over time and remains a major biological entity not only in Turkey, but defining large segments of entire global ecological system.

In Turkey and across large areas of the planet, wheat represents the homogenization of what were once much more diverse ecological systems. This loss of biodiversity was one of the main results of our agrarian practices, becoming exponentially more extreme with last century's industrialized agriculture, along with industry’s other great destructions of long established biologically diverse ecologies. The feedback signals of this destruction have been largely and continually ignored.

Schmidt's and archeology’s wrong-headed dichotomy of civilization shaped either by ecological forces or by the human mind is at this point dangerous. Dominance of the human mind over nature might be radically new for established archaeological thinking, but it has been standard practice for homo-industrialist for the past two and half-centuries. However, humanity and our technologically created environments remain and will always be part and responsible to greater nature – always.

Which gets back to the endlessly interesting question of just what was Göbeklitepe? Schmidt, for lack of a better term calls it a temple, most certainly an anachronism, but an acceptable grasping attempt to understand something new by using what we already know. Archeology discovered these enclosures, but unfortunately can never exactly provide their meaning. Of course this is where the greatest speculation takes place and no doubt when Göbeklitepe is better known, the mystics and metaphysicians will have a field day. Archaeological speculation is quite OK. It is essential to helping unearth harder insights. We just need to always keep in mind much of it will never be more than speculation.

So let's for a moment take Schmidt's idea that Göbeklitepe was a temple. A structure imparting human thinking and emotion onto the greater cosmos. As with all religion, an attempt to control the human perceived chaos of nature. Besides the structures themselves is the dominant representation in such a metaphysics of the wild animals surrounding and interacting with the people of the region. Most interesting, especially in regards to the overwhelming majority of temples across history to follow, outside the bent human arms and hands on a couple of the pillars, there is a lack of any other human form. However, in some of the younger, by several hundred years, Tas Tepeler sites, sculpted human likenesses are found in numbers.

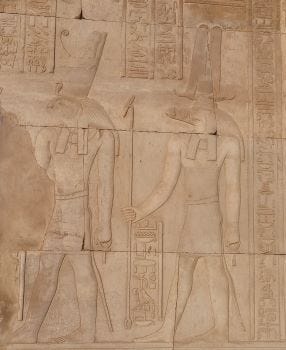

The sanctity of animals has long played a major role in human worship, including thousands of years later with the half-human, half-animal deities in Egypt, Mexico, and universally found in almost all ancient cultures. Ancient Egypt didn't appear until six-thousand years after Göbeklitepe, the Mexican civilizations nine thousand years later.

So what impact did Göbeklitepe have on human culture that followed? By 8000 BC, the site was basically abandoned. Intriguingly over the 1500 years of its existence, the enclosures were purposefully back-filled and buried. One certainly wants to think Tas Tepeler sites influenced what came after, yet the closest known agrarian settlement of Çatalhöyük, came five hundred years later, and lacks Göbeklitepe’s key feature, a temple, or a large public building of any kind amongst its scores of connected domiciles.

Agrarian civilization had separate beginnings in a number of places across the planet, including different parts of the Americas, Asia, and Africa. Recent archaeological insights reveal many of these first agrarian settlements lacked the centralized hierarchical structures of power popularly associated with the Egyptians, Sumerians, Mexicans and Han Chinese, among countless others. Unfortunately, we will never know the political structures of such distributed civilizations, but we certainly can understand the long agrarian roots of many of our present hierarchical institutions and much of our culture, roots severed from their original meanings and what should be increasingly obvious to all, completely insufficient for understanding more recent knowledge of nature and entirely incompetent in meeting the challenges of ever new technologies.

The most interesting facts about human cultural and technological development across the planet are not their dissimilarities, but their overwhelming similarities. All together they write the human story. The story of a relatively new species on a comparatively ancient planet. A story of our increasing knowledge of natural systems resulted in the creation of ever more complex and powerful technologies that in a very short period of time radically reshaped human culture, in many ways detrimentally reshaping the planet's environment. Knowing and accepting this story is essential to helping design a future where we would to choose to live.

Subscribe to Life in the 21st Century

History, Science, Energy, Technology, Environment, and Civilization